I saw the doors closing behind me: military green, school green, hospital green doors. My two friends stayed behind, smiling and wishing me good luck. If you had told me I’d never see the girl again, I wouldn’t have believed you.

I mean, I wouldn’t have wanted to believe you because, more than anything, more than tired, or nervous, or impatient, there was a part of me that was terrified, totally scared to death.

The doors swung softly closed. It had already started.

Actually, I wasn’t in any pain just yet, and that was my first mistake. When I got to the room, they gave me a green gown and a small vial. It is actually an appropriate welcome, if you take into account what’s in store for you: take off all your clothes, put on this shapeless dishcloth, stick this where the sun doesn’t shine…

Nothing there is designed to make you feel better. At least, for now, we were alone in the room. That’s something, I said to myself.

I don’t know you well enough to tell you what the enema was like. To sum up, I’m guessing it was OK: the first and last one of my life.

I was a bit sad that I wasn’t allowed to wear my own clothes, but the truth is that wearing my own clothes had already been a bad idea not long before. Of course, I didn’t have a choice then, and I didn’t have one now, either.

You see, this was December 2005, so 2005 was already in its death throes, so to speak. It was the night of the 30th, nearly midnight, actually, and we were in a very tall building in the middle of a pine grove. Before we got there, we had eaten in a place nearby, a restaurant by the side of the road. It was a typical Spanish restaurant called Sacromonte where they serve generous tapas. The four of us, as former Granada University students, found the name very funny. We knew the real neighborhood of the same name, and thankfully this was nothing like it: not as overpriced, not as dangerous, not as full of tourists. My two friends, in Cartagena for a short visit, had been putting up with my variable mood, between slightly hopeful and totally desperate. It was noisy, it was full of smoke. I have never been back.

We had time to finish our dinner, and just as we left in the car I had a strange feeling. I looked in the glove compartment, but it was full of the car’s papers and meaningless trash.

“Does anybody have a tissue?” I asked.

“I do, I do, I do!” laughed a girl I would never see again.

The night was clear, and the moon cast a very bright light.

I pulled my skirt and my underwear aside, and I wiped myself with the tissue.

“Right, to the hospital it is.”

We could see it from there, from the road. When we got there, it was nearly empty. The atmosphere among the hospital staff was festive: it was Christmas, after all. You could also tell that all the girls working the shift were extremely young. They were chatting and laughing. One of them took me to an exam room: I remember thinking she was cute.

“Take off your shoes and put your feet in the stirrups. There’s no need to take your skirt off.”

I am guessing I took my knickers off, but I cannot remember what I did with them. Maybe they were in my hand. At that moment, I was thankful I was wearing stockings rather than pantyhose.

It was cold in that room: suddenly the thigh-high lace and silicone band felt… not high enough. They were winter stockings: not just because of the cold, but because I’m quite clumsy and most times I rip the sheer ones before I set foot in the street. Buying thicker-than-normal stockings was a trick that a store assistant at the newly opened seven-story department store had given me with a conspiratorial air: “If they’re for work, if they’re for everyday use,” she whispered, “better buy the thicker ones: they really last. That’s what I do.”

Truth is, that wasn’t the first thing on my mind, at that moment.

“Nice stockings,” said the girl in the ER.

“Thanks.” It was the only thing I could think of saying. After all, if a cute girl likes your underwear, what can you say? I could dwell on whether she was secretly making fun of me, but I didn’t have much time to think about it back then – and now it just doesn’t matter.

As I was adjusting my shoes, I felt something wet sliding down my leg. When I stepped back, I found myself standing in a puddle.

“Is this… is this mine?” It was strange and sort of frightening, but I was more worried about not falling down.

“No, don’t worry, that’s from the girl before you. I think it’s better if you stay overnight,” she said.

When they gave me the hospital gown later on, I was glad I was not staining my own clothes, and not wearing anything out of the ordinary. They plugged me into all sort of tubes for a while, and then it got late. They sent me up to a room. That’s how the first night went.

The morning after, there were more people. At last, the gynecologist showed up. I do not know if the girls that surrounded her were the same ones as the night before. I suspect not. She put on some gloves.

“I don’t know if my waters have broken.”

“Let’s see.”

The feeling I had when she pushed was like sitting on the drain, in a bathtub. Gushes of warm liquid slid through her hand and pooled on the floor.

“Now they have,” she said.

Back to the room, back to the tubes and the drips. And back to waiting.

We waited all day. It hurt. But nothing happened.

It was New Year’s Eve.

#

In the evening they served dinner. My roommate had been watching TV all day. It was one of those TVs that sits in the center of the room. She had turned slightly to her side, which I didn’t mind at all. I would have preferred to have the TV off, but it had been on. All day. In a sense, it was like a buzzing in my ear. Not agonizing, just annoying.

At least dinner was good. I supposed they had made something special for Christmas, for New Year’s Eve. The food was good. It was plentiful and festive: roasted baby goat, dusty sweet polvorones, even the traditional Spanish twelve lucky grapes for the twelve chimes of the clock at midnight. The TV had been preparing people all day for the big moment, when people would eat one grape for each strike of the clock to see in the new year at the Puerta del Sol in Madrid. My man gazed at my dinner with a famished look. The food at the hospital cafeteria was way worse: I think he had been surviving on salami sandwiches. As there were only twelve grapes, we agreed on six each, and once I could eat no more he finished off my dinner tray.

At five to twelve the TV set in the room displayed the message “DAY PASS EXPIRED”.

The other couple didn’t react. We, on the other hand, were dismayed, despite not having been the slightest bit concerned about the TV previously. Yes, it had been a nuisance all day: the channel they had chosen was crappy. And it seemed surprising that with all those Christmas ads the TV channels couldn’t have spent a little more on the programs around them. During the day, we would have been grateful if they had turned it off. But right at that moment when we were about to welcome in a new year… That was different. I didn’t have to ask him to go buy a new TV card: he was off, but the vending machine was at the entrance to the building, and we were on the seventh floor.

He came back panting. When he finally inserted the token, the moment was over and the gala celebrations – probably taped months before –had begun. We shrugged and ate our grapes. The TV had credit again, but now we had paid for it and we had the power. A little later the four of us agreed that it was time to sleep.

And so passed the second night.

We had been there for two days already and I was starting to feel really desperate: but more than that, I was worried. I had been told that, in theory, you can’t go for more than twenty-four hours after your waters have broken without giving birth, since this might endanger the baby. Hour after hour after hour, we watched the paper roll out of the monitor and accumulate on the floor. Every once in a while a different person would come over. The lady gynecologist from the previous day. Another gynecologist, this one an old man. A midwife. A male nurse. They all looked at my medical history when they entered and made some sort of joke about it.

The contractions hurt. But the most annoying thing of all was the continuous influx of people that would come over, don some gloves, and measure my cervix with their fingers to check dilation.

Up until that day, I had known at least the name of every single person who had touched that part of my body between the vagina and the uterus. It’s a question of manners. “Good morning, my name is Jane Doe and I am… a matron, a gynecologist, a nurse, the cleaning lady…” I don’t know… something! But no: they didn’t even say good morning, or give their name, or explain why they were interested in that number of centimeters. In any case, it was clear that this was not moving forward.

But that was not the worst of it.

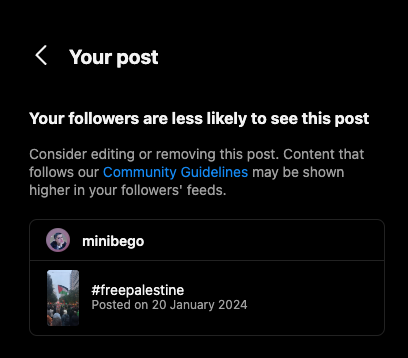

From the stories you hear it might seem that the aperture of the cervix would be a measurement available on one of the many machines that surrounded my bed. That, in the midst of all those technological advances that surround a woman giving birth today (monitors, artificial hormones, serum dripping into your veins) the measurement of the cervix would be just another sophisticated electronic procedure. But nothing could be further from the truth.

The cervix is measured by hand.

Literally, by hand.

A person comes over, snaps on a glove, and puts their hand into your vagina until they reach the cervix. And depending on the number of fingers they can place inside, and the dimensions, more or less, of that person’s fingers, you get a number in centimeters.

I discovered that the second time of many, many times they came by to measure it. I was unlucky: my labor had stalled, and they had to check it for hours, and hours, and hours.

The worse part was all those anonymous people coming, getting their gloves on and doing something to me that hurt a lot: touching my cervix. But after many, many hours of waiting, of putting up with my roommate’s stupid fascist TV channels, I was finally giving birth. Like I said, having your cervix meddled with hurts like hell. It doesn’t only hurt-–and it does, it hurts like hell–-it sets your teeth on edge. It’s like having a great balloon stuck up there, and it doesn’t only hurt when people move it, but it also makes a kind of sound and vibrates like somebody rubbing a balloon. Like somebody raking their nails down a blackboard. But you cannot hear the sound; you can just feel that vibration in your bones.

Once.

And again.

And again.

Around 2 in the afternoon, when it was already Spanish lunchtime, I asked for the epidural. I was scared shitless and had been hurt by the anonymous cervix massagers. So what would happen later, when the baby had to come out?

The anesthetist was late. When he got there, several lady nurses took hold of me. He wouldn’t talk to me, and the nurses spoke to me like a little girl. Sit down. Bend over. They surrounded me, half hugging me, half holding me down into submission, as they chatted about their stuff. The prattle floated in the air, like a cloud obscuring my view of what was happening around me.

The anesthetist’s head was just by my right ear. The nurse that held me from the front was by my left ear.

“What does this one speak?” he asked. Esta, he said. He didn’t say she. He said esta, which you would use for objects or animals or people that weren’t present or able to punch you in the face.

“I speak Spanish, English, German and Greek” I replied in Spanish, even if my posture only allowed me to look at the floor. “

The anesthetist made a weird sound, as if I had appeared out of nowhere. As if, all of a sudden, the cow the veterinarian was attending to had suddenly spoken.

“Spanish is fine.”

“That’s what I thought.”

People usually say that the epidural is a type of anesthetic, but people talk a lot of nonsense.

The epidural is an analgesic. This means that once it starts working, you lose sensitivity to pain from the waist down. However, all the rest of the sensations are there.

In my case I also lost track of the pace at which the famous cervix was opening. Although it is true that it no longer hurt when they came over to see if I had dilated.

So the good news is that an epidural is analgesic: it no longer hurt. The bad news is that the epidural is not an anesthetic, so I still got that feeling that people were rubbing a giant balloon that I happened to have stuck up there, deep inside.

The birth had definitely stalled, despite the oxytocin dripping in my veins. The monitor registered contractions that I no longer felt. It also indicated, through the rhythm of the heartbeat, that my baby daughter was, in principle, fine.

She was fine.

But that’s when we started to worry. After all, my gynecologist had broken the waters the previous morning: we knew it was dangerous.

The baby was still doing fine. That’s what the black line that had been undulating on the green-lined paper, pooling on the floor, had meant.

I was hungry, I wanted to eat something, to chew on something, to swallow, to feel the release, to have that rest. I wanted to take a walk, to distract myself from the background anxiety.

The girl was fine, but they wouldn’t give me anything to eat, in case we ended up in the operating theater.

The girl was fine, but given my situation it wasn’t recommended that I was disconnected from the drips or monitor.

Everything is fine, said the nameless faces that came in and out of the room.

The white-haired gynecologist came over. He put on his glove and I felt it again: the movement, the pushing, the rubbing of the balloon.

- Get her an –ine,” he said to a lady nurse that had appeared by his side.

“A what? Excuse me, what is that?” I said.

Again, I got that feeling of “the cow speaks!” The doctor turned to me, as if I had magically appeared out of the blue, as if, while being born, a baby had turned his head and asked him a question. He composed himself and answered:

“It’s a medicine.”

Now it was my turn to blink.

That’s right. Who am I? A five year old lost in an operating theater? A cow that just happened to pass by?

“I should imagine it is a medicine,” I said. “What’s more, I can see its box: right there, in that cabinet in front of me. Maybe I didn’t phrase my question correctly. What I want to know is, what does it do?”

“It is a muscle relaxant.”

“Thank you very much.”

Would no one treat me like an adult human being, of sound mind?

They injected an ampoule from the mysterious box I had been looking at all day. At the time I didn’t know, but that relaxant would make things worse.

After that I began to stop being aware of what was around me.

“Baby, you’re falling asleep,” he said.

“No, no, I…”

“You’ve fallen asleep again.”

“You’re here. I can’t… I can’t… Oh my, tell me something. I’m falling asleep, I’m…”

“Hello again.”

“What do we do? I can’t…”

“Come on, sing: sing with me.”

We were singing a song, but I couldn’t follow it. I fell asleep again.

“Hello.”

“It didn’t work.”

“No.”

The monitor kept reeling out the continuous paper. The stack on the floor was getting higher and higher.

The baby was fine.

“I’m afraid.”

And I was very afraid. I was afraid of opening my eyes and seeing something very different to the things that had been there when I closed them. I couldn’t stay awake. I couldn’t stand up. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t just wait, because I couldn’t stay awake. I couldn’t do anything at all. Hours went by, but all I can remember are moments of fear and blank spaces.

In the end, one of the girls that had come in during the last shift change said something.

“Eight.”

It was more or less 8pm, but she was talking about centimeters.

“Eight? Just two left, then.”

With ten centimeters you are all set. But it seemed like we wouldn’t make it to ten.

“Let’s go to the birthing room now. You’ve been here too long.”

We agreed on that in particular.

“Oh, one thing. It will be instrumental. Your partner won’t be able to be there.”

And in a sense, it was a relief, because what came afterwards was not pretty.

#

I do not know how, but I find myself in an operating theater. Through the little window in the door, I’ve seen him in the corridor with that paper green hat and those stupid-looking green socks. In a sense, I am glad he is not here. This would be too much for him. It’s too much for me. The two gynecologists have arrived: the communicative one with the white hair has some kind of industrial vacuuming machine with him: it has an ugly long tube. The lady that broke my waters yesterday is up near the stirrups with me. My back is on the table and my feet are up in some metal stands. I cannot move, except for raising my head and my torso a little bit. It’s not like I could move any other part of my body anyway.

I remember flashes.

The gynecologist in front of me works the machine that looks like an industrial carpet vacuum cleaner. In English you use the word “vacuum”, but in Spanish it’s called a sucker. And it’s a nasty sucker, at that. I don’t know how he’s positioned it, but I know that it feels like a bathroom rubber plunger moving to and fro against an over-inflated balloon. I get the impression I can hear the sound of a scratched balloon over the hum of the machine.

They pull, and pull, and pull.

“Push, push! Push when you have a contraction!”

With the epidural I just don’t know when I’m having a contraction. They have to tell me when they see it on the famous monitor. I don’t even know where the monitor is now. Has someone cut the used paper before bringing it here? Is it here, somewhere? I don’t see it.

“Push now!”

I am pushing, but I don’t know if it is of any use. I cannot feel anything except the very, very, very strong sensation of the balloon being rubbed. She is stuck. Is she all right? Will we ever get out of here?

“OK, one more and we go to cesarean section.”

“Push! Come on, push, now!”

“I am pushing!”

“Push! Push! Push from your butt! From your butt!” shouts the nice gynecologist at the top of her lungs, towering over me. And she pushes my belly with her forearms, while the other gynecologist pulls from the other side.

I look to the door. There’s no one. Thank God: thank God that they did not let him in here. He wouldn’t stand seeing this. Shouting. The balloon. People everywhere.

“We’re going to cesarean section.”

“One more.”

More shouting. The machine roars. This girl I’d never met before who claims to be a gynecologist has her hands firmly planted on my belly, and is pushing down. As for the gynecologist gentleman… I can barely see his white hair: he looks like that detective doctor on TV.

“Let’s take her up now. This isn’t working.”

“One more.”

I think the TV doctor guy was funny. This man doesn’t look funny to me, or indeed inspire any kind of trust in me. That’s it. I promise I am pushing.

#

Who is he, what’s his name, what kind of things are they doing that I’ll never know about? I see his head between my knees, pulling, pulling and pulling. The machine keeps humming. I look at it and it kind of seems like half an R2D2, but gray. Half an evil R2D2.

“Here you are: your daughter.”

He places a chunk of slippery, dark meat on my belly: it looks a bit like a hairless cat rolled in butter and bathed in blood. It weighs more or less the same, and it is very slippery. Please God, don’t let her slide off onto the floor, please God don’t let her fall.

Her back is facing me and I cannot see her face.

Don’t let her fall down. She slips: we’re both slippery. I’m terrified that she might fall to the floor.

“My daughter, my daughter, my daughter, my daughter.”

I’m crying.

The next flash is the now familiar face of the gentleman with the white hair. His head is once again between my knees. The placenta comes out and is carried away. Now he looks between my legs with interest.

“We were saved by the bell there,” he says with relief. We?

I feel tiny pulls, as if someone had stuck little pieces of duct tape to some clothing I’m no longer wearing, and is now pulling them off. I realize that he’s sewing me up when I see his hand raising the needle and thread. He sews intently.

He looks at the result.

“No. Nope…”

With some sort of instrument he takes all the stitches away again. Deep down, I’m glad. Since he didn’t seem to like the result, it’s better if he does the whole thing again. With a determined gesture, he sews me up again.

#

In the meantime, my daughter is somewhere else. Where is she? A bit later they take me to a white room. Here they are, both of them, my newest closest family. They’re both wearing hats: he’s wearing a green one; she’s wearing a white one. She’s awake, calm, with her eyes wide open. She’s inside a white transparent box. I’m wondering if we both look happily stoned.

I want to take her in my arms. Her face is puffy and red. She’s my daughter, but I’ve never met her before. Her face is not familiar. It’s a weird feeling.

I put her at my breast, like I’ve been told a thousand times, like I’ve read everywhere.

A nurse comes a bit later.

“Oh, there you have her. That’s what I came to say.”

I’ve got her. Everything has gone well, I think. I can breathe now, calm down now. Everything has gone well.

I am wrong, but I don’t know that yet.

I’ve been a mom for three hours now, a mom to this little ball wrapped in a sheet, and I am a bit lost. She cries and it’s normal, but the whole hospital is asleep. It’s midnight. Most likely she’s hungry. We try to calm her down with our four hands but it doesn’t seem to work. I put her at my breast, but that doesn’t work either. I’m probably doing something wrong, but I do not know what it is. Finally, a nurse shows up. I imagine she’ll want to help with breastfeeding, or tell us to go somewhere where we won’t wake my roommate or her baby.

“Here, give her this.”

“A bottle? But, the breastfeeding…”

“It’s nothing, there’s no harm done with just one bottle. Give it to her. She’s hungry.”

I give her the bottle. She falls asleep.

It is so soon that we do not know if what we’ve done is right or wrong.

#

The morning after, when the pediatrician looked over the baby, he gave us the news.

“Her collarbone is fractured. It’s normal.”

A fractured collarbone? I didn’t recall that being very normal, but who am I to say?

When the little hat they dressed her head with in the labor room fell off, we saw that the skin on the top of her head had been scraped away: just like when you graze your knees when you fall off a bike as a child, only all over her head. It was a direct consequence of using the vacuum to get her out. But we couldn’t imagine that her collarbone would be broken. Was that why she cried?

They took her away to confirm it with an x-ray.

The pediatrician, a nice young man, came back and said that the x-ray confirmed the previous diagnosis.

“You don’t want to see the x-ray, right?”

“Why wouldn’t I want to see it?”

I found the question weird, because I’ve seen every x-ray that I’ve had, and I’m guessing that is the normal thing. It was my job now to take care of my baby’s health, until she could do so for herself. Maybe I wouldn’t be able to grasp the whole meaning of what I saw, maybe I would not be able to interpret it correctly, but that was no reason not to see it. Maybe I would only see a thin black line running down the bone, and somebody would have to explain to me where exactly it was broken. How weird all this was.

“You sure?”

“Hmm, yeah? Sure.”

He showed me the x-ray.

They had broken her bone. They had broken it badly. They had broken a bone taking her out. It was as clear as the light of day. It was so clear I get scared. It was like a little broken twig, the tips clearly parted. Like railway tracks at a junction, the two sides of the bone point in different directions, up and down. They did not even touch each other.

My girl, my broken girl.

Inside, little by little, my heart crept back into its place while I kept calm. It was a bit like walking over a step on some stairs that suddenly is just not there.

Bit by bit I came back to normal.

“This fracture is totally normal. It will heal on its own, without leaving a trace. Maybe when she’s older, touching the bone, she will feel a tiny bump, but it’s nothing.”

Fracture. Fracture not fissure, I corrected myself mentally. Nothing, he says.

I’ve got to listen better, now that I’m doing it for somebody else, I thought.

“We’ll give you a referral for a few months of rehab. She’ll tend not to use that arm, so it won’t hurt. In rehab they’ll stimulate the nerves in that arm so she moves it, with some tiny brushes, with sponges… you can do that at home too. In the meantime, just don’t lay her down to sleep on that side.”

My girl, she had been crying.

#

Now, on every birthday, I look at the mom, who was actually there that day too. The day in which, as if through a dark and incomprehensible magic, she started feeling the pain in somebody else’s body too.

That day I finally understood that every birthday is the anniversary, not only of someone being born, but also of somebody giving birth.

Congratulations.

END

Amanda wants you to sing along — right?

Amanda wants you to sing along — right?